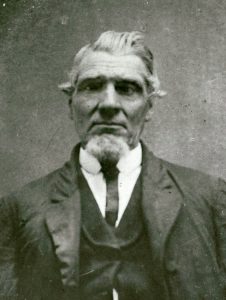

Photo Credit: Church History Library

Unfortunately for William and his family, his joy in the Restoration faltered each time his anger got the best of him. Joseph wrote of his anger by saying, “The wickedness of his brother [William], who Cain like had sought to kill him.”2 Although there was a brotherly reconciliation, William’s temper remained an issue. On November 3, 1835, the Lord revealed to Joseph that William had the potential to succeed in the Lord’s kingdom if he would repent:

I will yet make him a polished shaft in my quiver, in bringing down the wickedness and abominations of men, and there shall be none mightier than he, in his day and generation, nevertheless if he repent not speedily, he shall be brought low, and shall be chastened sorely for all his iniquities he has committed against me.3

William’s repentance was only momentary.

On May 4, 1839, at a general conference of the Church held in Quincy, Illinois, William was asked to “give an account of [his] conduct, and that in the meantime [he] be suspended from exercising the functions of [his apostolic] office.”4 The suspension imposed upon William was lifted when he was called to serve a mission in England with other members of the Twelve. William did not serve that mission, excusing himself on the basis of poverty:

I do not wish to exonerate myself from all blame, but merely wish to state the circumstances in which I have been placed. . . . I can assure you, that it is not because I have any doubts respecting the work of the last days. . . . Unfortunately for me, poverty has been my lot, ever since I was called to the ministry.5

In April 1841 William accepted an assignment to journey to the Eastern States to gather needed funds for building the Nauvoo Temple. Extant Church records show that William pocketed the collected funds for his own use. It is purported that the last time he saw the Prophet Joseph, he threatened him with violence.

Following the martyrdom of Joseph and Hyrum Smith, William supported the leadership of the Twelve: “My advice to all . . . uphold the proper authorities of the church. . . . I mean the whole, and not a part: the twelve . . . the whole twelve.”6 In October 1844 Brigham Young wrote to William that in addition to his service in the Quorum of the Twelve, he would also serve as Patriarch to the Church. “I must say I am very thankful,” William said. “The legal right rests upon me.”7 William was ordained Patriarch of the Church on May 24, 1845. Five days later, Brigham “prayed that the Lord would overrule the movements of Wm. Smith who is endeavoring to ride the Twelve down,” asserting that his position as Patriarch gave him the right to be President of the Church.8

William was excommunicated on October 12, 1845, for using the “public funds of the Church to his own private use—for publishing false and slanderous statements concerning the Church and for a general looseness and recklessness of character which ill comported with the dignity of his high calling.”9 William wrote of his excommunication and of the Twelve, “I Know them to be wicked men and infernal Scoundrells and they Cut me off.”10

Over the next few years William was acknowledged as a Strangite apostle and patriarch and organized his own church in Palestine Grove, Illinois, and again at Covington, Kentucky. At the outbreak of the Civil War, William enlisted in the Union Army. After the war he wrote to Joseph Smith III, president of the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, requesting an appointment in his first presidency. Although the request was denied, William joined the Reorganization. He died in 1893 in Osterdock, Iowa, at age eighty-two.

By Susan Easton Black, cross-posted with the permission of Book of Mormon Central from their website at Doctrine and Covenants Central.